Over the last couple of months, I helped launch a long asked for service: Content development. To our surprise, by simply adding it as a question in our checkout, we got a healthy flow of content work. Roughly 90% of those projects asked for help to write their fundraising pitch.

I’ve been the primary author and editor for all of our pitch deck writing projects. I work directly with the executive team (often the CEO, their direct reports and sometimes some board members) to help turn their business and knowledge into the best pitch possible.

It has been exhilarating to work on all of these ventures and help the founders achieve their visions. Many of the projects have been Series A fund-raises (around $10M – $30M), as well as helping some venture funds raise money and even the creation of a new National Museum.

In this article, I’m going to share what I’ve learned from this experience – how to best transform vision and knowledge into an inspiring pitch. I’ll include the different approaches, what has worked and not worked, and reflections on what makes a good fundraising pitch.

What makes a good pitch?

Let’s first think about the overall end goal: our clients are trying to raise capital. The investors may be anything from individuals (“angel investors”) to small seed funds, larger VC funds and even up to institutional investors (think pension funds and universities that have large amounts of cash to manage).

One upfront thing every pitch needs is clarity of what the proposition is. Y Combinator drilled that into us during demo day, with Kevin Hale giving a hilarious and spirited talk on what not to do. If nobody understands at the get-go what your company/fund/project is, then despite smiling and nodding, you will not get any investment.

For any investor to write a check, there are generally two further critical things:

- The facts: The investment opportunity has to line up with the stage, sector, country and check size that the investor has a mandate for. After those basic tests, the hard facts need to all be in place: Do the unit economics, traction, team, product, legal structure, current runway, etc. all pass muster as solid and good enough for the investor? Much of this is information that will need to be summarized in the pitch deck to allow the investor to do a first-pass filter of the proposition.

- The emotion: I’ve personally observed many times that it’s excitement (and sometimes FOMO) that gets a deal over the line. Many investments carry a lot of uncertainty – when seed investing you often have little more than a vision and enthusiastic founder to go on – and it’s those deep seated human emotions that carry the deal through. Emotion has been the driver of many legendary early investments, as well as the reason for often-lambasted herd mentality and irrational exuberance.

At a very simple level, the front of most pitch decks sets up the unique story and urgency (the emotion) and then the latter 2/3rds take care of the facts.

Unsurprisingly, the emotional part of the pitch is the hardest. You need to take the whole company (or project) and find the threads of a great story within it. You need to write something that is easy for newcomers to understand, is memorable and is exciting.

It is often this first part that takes up the vast majority of the pitch writing time and contains many iterations, different concepts and long discussions. Once you discover a good story arc, though, it really is quite magical – this is when the whole pitch quickly comes together.

The starting point

Clients come to us from many starting points. Usually there is an existing slide deck, but some clients don’t have a pitch deck yet. In the latter case, they often supply other materials, like a website or sales presentation.

Often, clients also have limited branding guidelines. It’s not unusual for a client to simultaneously write their Series A fundraising pitch and give themselves a much needed design facelift at the same time. In these situations, the design team can start brainstorming whilst I work with the client on their pitch content – then once the content is ready, we can transform it into their fancy new look and feel.

The pitch transformation process

Every project is a bit different, and I tailor the process around each client’s needs. There are a few common patterns to this work, which I’ll describe here.

The simplest and fastest projects are where I simply provide feedback on a call and perhaps also in writing. In these, I check that the pitch meets my criteria of clarity, emotion and has all the important facts. (I’ll talk more about what those consist of later in this article.)

Many founders come to me and say “I’ve spent so long looking at this in a vacuum, I really need some fresh 3rd party eyes!” It’s a common situation, as they know their business deeply – making it hard to know what will make sense to someone else. As part of the pitch writing process, a big focus is on: “Is this clear? Will a third party quickly understand this and get excited about it?”

Most clients look for more hands-on assistance. For these, I’ll take their existing materials and eventually edit and rewrite them into a new pitch. Before doing that re-writing, though, I usually have a long zoom call where I gather context and go through their current pitch in detail.

For context, it’s helpful to understand questions like:

- How much are you raising? From what sort of investors? Knowing audience expectations helps guide the level of detail. If we’re pitching to institutional investors, there needs to be a lot of financial rigor. If this is a seed raise, we need to focus more on the story.

- Is this being sent out to people, or will you always talk through it? If it’s always presented, we can shave down the content to be less distracting. If it’s sent ahead of time, then it needs to be self-standing.

- How engaged is the audience? Is this their first time learning about you? This guides how skim-friendly the pitch needs to be. Most often, we’re building a deck for a first time encounter, and it’s being sent ahead to them. In this case, it’s vital every slide tells a clear and important point, and we give just enough to be tantalizing without being boring or overwhelming.

Once those context questions are out of the way, we move to capturing the core of the proposition and its pitch. If there is no existing pitch deck, I’ll ask one of the team to give the pitch verbally. If there is a pitch deck, we usually talk through every slide. I want to learn:

- What is this proposition? I need to thoroughly understand this so that I can ensure we have a simple and accurate description of it.

- What gets potential investors excited? For every proposition, there are a few particular things that really light up their potential investors. For one company, it could be their smart unit economics. For another, it could be the philanthropic vision.

- Does each slide work? Does the client like it, or skip it? What do they wish was different? Often a ton of helpful changes get figured out here. It’s really telling when the client hates a slide and always skips it – this shows that slide needs re-written. This is also a great junction for me to insert my ideas and challenges around the content and get client buy-in to the changes I’d like to make.

Cracking the “vertebrae” is important

Way before every Y Combinator Demo Day, there are “Vertebrae hours” where the founders sit down with a partner and try to write the core (or spine in this metaphor) of their pitch. This is:

- The tagline that succinctly describes the proposition. Examples include: “Turning open water into efficient agriculture” or “Preventing software bugs before they are deployed”.

- The most salient points of the pitch for an investor, e.g. “Industrial farming cannot keep up with the projected demand for animal protein in 2030 / We are able to deploy humane farms to open water for comparable price per animal / We already have $100M in client commitments”.

Getting the tagline and core points figured out is the first, and most essential part of the pitch writing process. Once you have good answers to these, the foundation is ready and you can quickly build the rest.

Depending on the client, much of this is already worked out as they’ve been through previous investment rounds. However, it’s common for the tagline to be missing or hard to understand – we often spend time creating a better one.

By asking a lot of questions until I understand the company well, I can then usually brainstorm a list of taglines. They should be self-standing, so a third party can read one and instantly know what the investment proposition is. For tech companies the tagline is usually close to a description of their product, although usually a bit of the market opportunity gets woven in. (“Educating the next 8bn humans” or “Reducing the cost of solar by 30%”)

Getting the initial story right

Once the vertebrae is known, the next step is to think about the story arc of the presentation. This differs depending on the nature of the proposition (e.g. raising money for a venture fund doesn’t quite fit this pattern), but most commonly contains a problem-solution-product triple.

This is a really effective storytelling formula as it sets up urgency (the problem), then resolution (the solution), painting the proposition in a great light. Then, it finally solidifies the solution by going into deeper product detail.

Whilst this may sound constraining, there is endless creative scope within a problem-solution arc. For some pitches, a lot of education and demonstration of the problem is needed. For others, the problem is so obvious that the solution takes up most of the space to shine.

For some propositions – particularly complex technologies – it can take a lot of work to find a problem-solution pair that is both accurate and understandable. Often we wireframe out diagrams to help tell the story, with lots of squiggles and doodles for designers to later tame. When doing this sort of illustration work, it’s helpful if the problem-solution-product illustrations share visual elements so that the reader can quickly understand how they fit together.

Taking care of the rest of the deck

As I said earlier, after the first emotion-driving story, the rest of the deck is more focussed on sharing key facts about the proposition. These most often are:

- What product/service exists today

- How defensible is this?

- Is there a capable team in place?

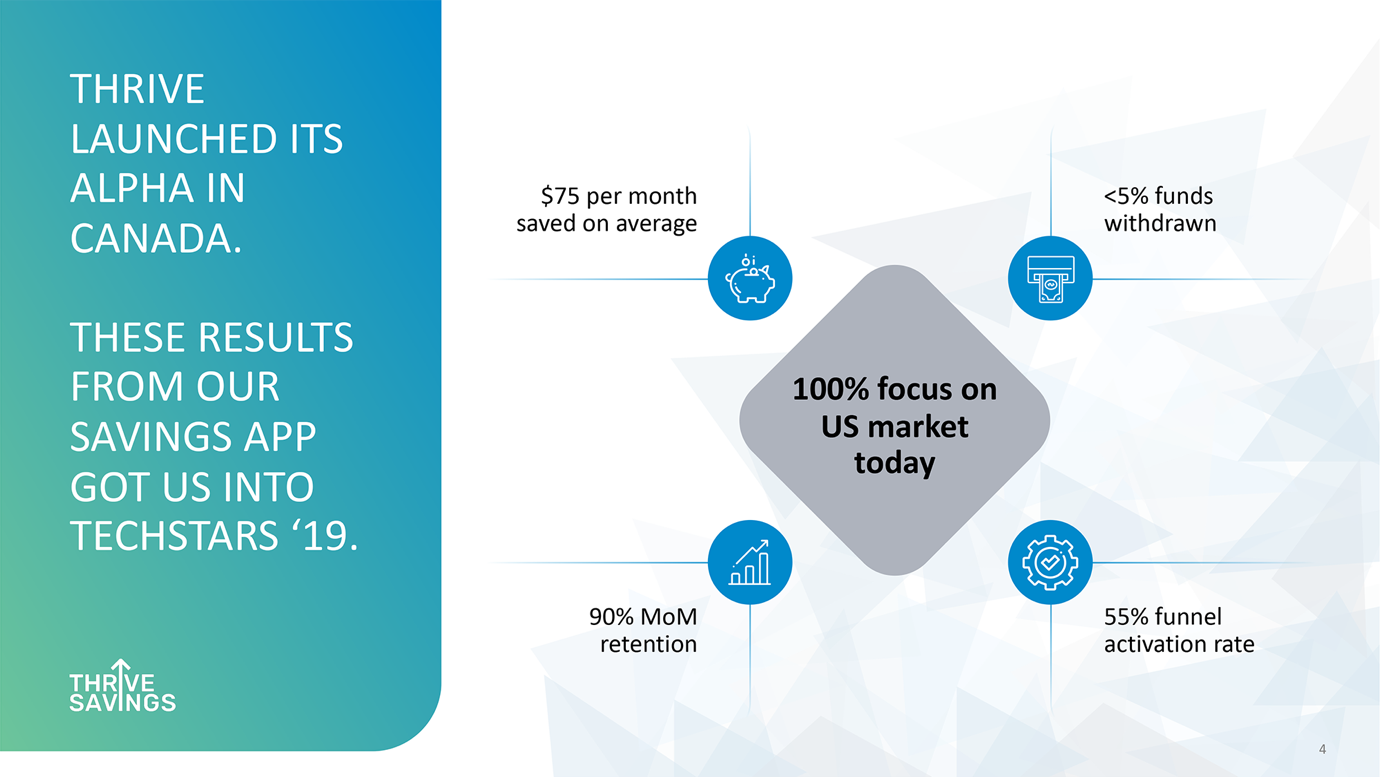

- Is there existing traction to prove product-market fit?

- Do the business fundamentals (CAC, churn, unit economics, etc.) look good?

- Is the market big enough?

- What is the fundraising ask and how will it be used?

Each of these facts benefits from supporting evidence – CVs of the team, growth graphs, product screenshots and more. I help the client identify the best evidence they have on hand and effectively present it in their pitch through words, illustrations and graphs.

This part of the deck is usually quite quick to outline, although it requires some homework time for the client to collect the necessary evidence. Where I have an idea of a good piece of supporting evidence, I include an invented placeholder in my outline to show what is possible.

How to turn the ideas into words

With all this understanding, ideation and resource gathering under way, we’re ready to start getting the pitch down into digital ink. I usually use a Google Slides document with zero branding so we can easily iterate on the content and have a clear latest version.

My personal writing style (which can of course tailor to the audience and client) generally focuses on clear, punchy impact statements beside illustrations and charts. I find this works really well for what we want to communicate and the length of the document.

The first step is then to essentially build a presentation of just titles. I like to make every character count, so I avoid generic titles like “Our product” and “Finances”. Instead, I try to tell a story with titles like “We’ve released a suite of 5 apps” and “We profitably acquire users for $23 each”.

Once those titles are together, I usually wireframe what is to go with them, copy-pasting from existing documents where possible. Together, this forms my first outline to get feedback from the client.

How to effectively collect and apply feedback to a pitch

If working with clients is like herding cats, being a pitch deck consultant is like herding cats with big job titles and limited time for herding. I try to be very organized so that each feedback session answers all the current unknowns and unlocks my next editing cycle.

Clients differ in how they like to give feedback, and I happily let them use whatever avenue they like best. Some reply with long linear emails, many drop pins in our platform (my favorite as it keeps things organized), and some jump into Google Slides to edit and comment there (also very effective).

It’s really easy for feedback sessions to wander, introducing lots of open questions and reducing certainty of direction. It requires a delicate balance between letting creativity and ideas flow, hearing out everyones’ feedback, and keeping the project on track to deliver an investor-ready pitch.

To combat this, I make sure I have a clear list of questions and client-actions for each call and continually review it so that not only are all my questions answered, but someone is assigned for each piece of client homework. After any long discussion, I suggest concrete action points and push a decision of whether to make said change.

I also open up most feedback sessions with a high level review question: Does the overall flow hit the mark? Are we mostly happy with this direction? Usually the answer is yes, but this is an important check. It ensures that later, when I’m directing us to action points, I know we’re not overlooking any elephants in our Zoom room.

A final note on feedback: Ask ten investors for feedback on a pitch, and you will get at least ten different answers. At YC, Sam Altman stressed that you usually need to attach to a few main feedback providers. If you try to satisfy everyone, you’ll drive in maddening circles.

How do you know if a pitch’s content is ready?

Q: When is a pitch deck ready?

A: We needed it yesterday!

Pitch decks usually are on the critical path to an even more critical activity: getting cash in the bank. It’s important not to waste time, which is why we set timeline expectations based on our experience at the start of every project.

Broadly speaking, it’ll take about two weeks to do a deep rewrite of a pitch deck. This sounds surprisingly long, but it doesn’t take many cycles of waiting on feedback and data from the client to fill that time (10 business days). I do my best to provide next day turnaround once I have what I need.

In reality, no pitch deck stays the same during the course of fundraising – they continually evolve based on investors’ questions. Usually as investors get more serious they have more detailed asks, and often the deck has a bunch of slides added to answer these.

So, when is a pitch deck ready to first go out to investors?

I generally look to two sources to answer this:

- Does the client feel that this is a good pitch of their proposition?

- If the client has some friendly investors/advisors, have we incorporated their feedback?

Once those two sets of stakeholders are satisfied, it’s a good point to start driving around Sand Hill road scheduling Zoom calls. You can always adjust the deck more later.

How do you both write and design a pitch effectively?

It’s important that after writing a good pitch, it also looks sufficiently professional. The quality of pitch deck design has been steadily rising, and people increasingly equate good design to good companies. I’ve a lot of experience with helping get pitches written and designed, and offer these tips.

First of all, you want to separate into two main steps. Get the content down, then do the design. Every time I’ve seen these steps mingle, it leads to extra work and confusion. Therefore, do your best to hold back on design until ready and you’ll probably save some time overall.

That said, you can start planning for design from the get-go. This includes:

- Exploring different looks and feels for the design (we call these “style samples”)

- Getting your brand assets together (e.g. high res logo files) or created in the first place

Then once the content is ready your designer can zip the look-n-feel with the content quickly, delivering a pitch-ready presentation.

As is inevitable, though, some content changes spill over post-design. Usually the founders edit the presentation file directly, and dent some of the design polish. We pass these through the design team again, who apply a polish cycle and get the slides back up to par.

Top tips for writing a good pitch

With all that said, I’d like to provide you with a TL;DR guide to writing a good pitch deck. Nothing is a true substitute to all the work I outlined above, but here are the main principles I encourage you to follow:

- Think about why your proposition is unique and exciting right now, and use that to guide the start of your pitch

- Get really clear on your tagline and top three selling points to investors

- In as few words as possible, make those points

- Include a lot of factual evidence for your claims and viability – successful pitches tend to have solid backup for their progress and future plans

- Get feedback on your pitch from potential investors and incorporate that feedback

The final slide

I hope you enjoyed this whirlwind tour of pitch-deck writing. It’s a pleasure and privilege to work on these projects, getting to help shape the narrative of a company at a critical moment. Every project teaches me about a different industry and prompts reflection on the nature of storytelling.

If you’d like to learn more, check out our growing library of pitch-deck resources. And if you’d like us to work our magic on your pitch deck, then please do get in touch!